How the Alchemist of New England Became a Legendary Counterfeiter

Glazier Wheeler turned his skill for manipulating silver into profitable schemes.

The year was 1789 when an old man shoveled dirt onto two hefty barrels of silver, hidden away in a cave on the roaring banks of the Swift River in Massachusetts. He needed to bury his treasure, because he had procured it by means that were considered illegal and, at one point, mystical. This old man was Glazier Wheeler, once a blacksmith and engraver, but the town of Dana knew him as the “alchemist.” Wheeler spent his life practicing the art of converting “base metals” into silver through chemical reactions. By the late 1780s, his barrels were the culmination of a lifetime spent manipulating the silver content of coins. Wheeler’s buried treasure engraved his name in the criminal history of New England as a godfather of counterfeiting.

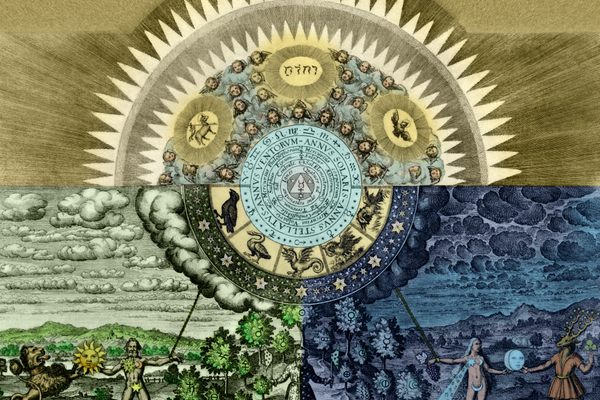

Wheeler had a monomaniacal obsession with silver. He began his career as a respected metalworker in Newbury, New Hampshire, and developed a preoccupation with the belief that cheap metals, such as pewter and brass, could be “transmuted” into silver—in other words, alchemy. Alchemy had been around since the medieval era, and in the 1600s, the Puritan elite of Boston had been proudly obsessed with the process of alchemy as a spiritual exercise. But by the 1700s, it was becoming more scientific—alchemists were becoming chemists.

Wheeler was never able to conjure gold, but he learned he had an unmatched skill for manipulating silver. His “alchemy” then became utilitarian exploitation of a fad rather than a supernatural talent. To those uneducated in chemical processes, Glazier’s trial and error work looked more like medieval magic than scientific experimentation. Wheeler understood that by branding him an “alchemist,” the public identified him as one who had a talent for manipulating money.

At the time, there was high demand for metallic coins and little law to enforce penalties for manipulating currency. Paper currency, a minor novelty in the 1760s, was distrusted in rural areas, as it fluctuated widely in value and was subject to expiration dates. Wheeler had become adept at illegally minting silver dollars (known as “half joes”) at the rate of three or four fakes to the cost of one standard dollar during his time in Haverhill, New Hampshire. He even offered his services in 1768 to sell $60 worth of “stamps and tools” that could produce false silver dollars.

He was only discovered when he pressed his coins so thin as to retain only half the silver content of a legitimate coin. A New Hampshire court order was issued in 1783 ordering that Glazier Wheeler be arrested and have his ears cut off (“cropt”). Wheeler eluded the local sheriff then headed south to continue debasing coins.

Thereafter, he became a regional legend in New England. He remained active in remote areas, such as New Salem in Massachusetts, where he could freely distribute both chemicals and metal “dies” (hollow molds used to cut shapes for coins) to other counterfeiters. By 1784, Wheeler was associated with con artist Stephen Burroughs who would describe Glazier Wheeler in his Memoirs as “Credulous to the extreme… He had spent all his days in pursuit of the knowledge of counterfeiting silver, so as to bear the test of essays.” These tests proved the legitimacy of currency by sensory or chemical reaction, but Wheeler was talented at defrauding them. Such “essays” included examining the color of coinage to prove quality, weighing coins to prove silver content, tapping the suspect coin to hear the resonance of metal, and applying chemicals like vitriol (sulfuric acid) and aqua fortis (nitric acid) to dissolve the metal content.

“There are guides published in newspapers and as pamphlets on how to sort the value of these different coins, what they might look like, and how they can be compared,” says Zachary Dorner, a historian at Maryland University. “Newspapers tell people what a certain coin should look like, what color it should look like.”

Wheeler and Burroughs were finally arrested for attempting to pass off counterfeit coins at an apothecary in Springfield. They faced a dramatic trial in 1785, then the two were imprisoned in the Castle Island prison in Boston Harbor. After release, likely around 1788, Wheeler drifted to the area of Dana where he spent the rest of his life fiddling with “pewter dollars” and forged bills in his cave, living out his legacy.

Alchemists had long attempted to turn different elements into gold, silver, or money in general. It seems fitting that, as science improved and alchemy began transitioning into chemistry, the practice turned to forging coins. Likewise, people on the other side of the law were using the evolving chemical science to thwart counterfeiters.

At the same time that Wheeler was running his criminal schemes, Benjamin Franklin was already experimenting with standardized “safety features” for currency in Pennsylvania. Franklin’s experiments developed the use of chemical safeguards like graphite-based black inks, which are harder to produce than the common vegetable oil–based inks. He also helped create “nature printing,” which uses prints of natural leaf patterns on banknotes, since engravers were unable to replicate the natural complexity of vegetation. Printing trade secrets developed to keep counterfeiters like Wheeler from reproducing the quality of a centralized paper currency.

The “essays” using vitriol and aqua fortis evolved into modern ultraviolet light and starch tests. Coin counterfeiting has largely been replaced by banknote counterfeiting due to the increased values and easy access to presses. The main concern today is the quality of the fraud. On today’s money, “you’ve got holograms, you’ve got embedded materials into quasi-fabric printed contexts, so it’s a lot harder to necessarily expect quality,” says Thomas J. Holt, professor of criminal justice at Michigan State University. Holograms, which present a pseudo-metallic safety feature, are present on most banknotes through minuscule “security threads” that react to light tests. That doesn’t stop fakes from replicating security threads and watermark designs to pass ultraviolet tests, according to the Secret Service. Vendors who sell counterfeit money online even claim to include “Intaglio printing watermarks” and “special foil elements, iridescent stripe, and shifting color” that painstakingly replicate ink-based and holographic security features in their copycat designs.

The fabric must also be experimented on to subvert chemical tests. Security threads are woven into dollars to prevent “bleaching,” where cheaper bills are washed with bleach then illegally reprinted as a higher denomination. If the security thread does not match, then the bill was likely altered by some process. U.S. currency is printed with no wood fibers or fabrics, which differentiates the material from other standards of paper. Since readily available iodine pen tests react to the presence of starch in the paper, counterfeiters are known to chemically “wash” starch out of their materials.

One could say there’s a significant amount of chemistry involved in transforming regular materials into gold.

For Glazier Wheeler, creating false currency was both magical and economic. Wheeler’s alchemical treasure in Dana has never been found. However, it seems his legacy has carried on, for better or worse, in today’s modern alchemy of counterfeiting.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook