Killiansburg Cave

A cave on the Maryland border where civilians took refuge during the bloodiest battle of the Civil War.

Caves played several roles in the American Civil War. As the source of saltpeter (or potassium nitrate), Appalachian Mountain caves provided much of the gunpowder used in combat. And occasionally, runaway soldiers and civilian refugees found a safe hideout in these rocky caverns.

In 1862, as the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, the Battle of Antietam, began to unfold in their backyards, some residents of the border town of Sharpsburg, Maryland, took refuge in a nearby rock shelter called Killiansburg Cave.

Central Maryland’s karst topography is studded with small caves. Thousands of years of erosion has created towering, Gothic limestone bluffs along this stretch of the Potomac River. Some bluffs are pockmarked by dark, eerie openings in the rock. A couple of the caves are tiny — about the height and width of a human being — and reach back deep into the bluffs.

There’s no great spelunking to be done here, unless you want to plunge deep into history.

By the time the Union and Confederate armies began to converge on the rolling wheat fields around Antietam Creek in September 1862, many townsfolk had already fled Sharpsburg on foot and horseback. Some made it to Killiansburg Cave (technically a rock overhang about 20 feet tall and 35 feet deep) two miles west of town. The spot sits directly on the river, and at the time was right on the border between North and South, facing into what was then Virginia, now West Virginia.

Half-deafened by artillery thunder, terrified refugees huddled under the overhang as shells careened into trees nearby. African Americans also took shelter in the cave and along the river, most likely including several fugitive slaves, fearing retribution from the Confederate Army.

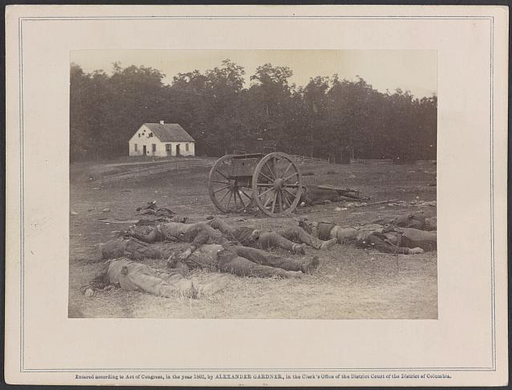

One family fled to the cave with an old pony. When the battle was over, they set out for home. A daughter remembered that her family and the pony had to step over countless hideous corpses strewn thick around the area — about 7,000 men died in the battle or of their wounds.

Coming back from the cave, civilians found their houses burned and farms wrecked, their horses stolen and livestock butchered to feed hungry soldiers. One man walked into his home and found the grisly remains of two Confederate soldiers inside, men who had “literally been torn to pieces” by a shell that came through the wall – one of them still clutching a bunch of onions.

Confederate sharpshooters, unsure of who had won the battle, stayed behind in the trees. One girl recalled that the only way they got them down was to leave homemade bread and peach jam on the ground, luring them down with the sweet scent. “With the smell of it,” she wrote, “they came down and gobbled like animals.”

Know Before You Go

Killiansburg Cave sits at mile marker 75.7 on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal towpath, 2.5 miles each way from the parking lot. Long abandoned, the C&O is now a hiking and biking trail stretching from Washington, D.C. to Cumberland, Maryland. (A connecting trail goes all the way to Pittsburgh.)From Ferry Hill visitor center by the bridge to Shepherdstown, West Virginia, you can walk or bike north for about mile to reach the cave. It sits up a steep hill 100 feet back from the towpath. Several tiny caves, sometimes called Snyder's Landing Caves, are also visible from the towpath nearby.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook